When coming to Botswana, a big question is, “what about malaria?” Malaria is here for sure, but what is the risk? You can take antimalarial drugs, but they have their own side effects. Lariam has especially horrible side effects: severe anxiety, paranoia, hallucination, depression, restlessness, confusion, and unusual behavior, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. I hear it also causes nightmares. I decided in about 2 seconds to avoid Lariam and never give it to my children. But I was still worried about malaria, a serious, sometimes fatal disease.

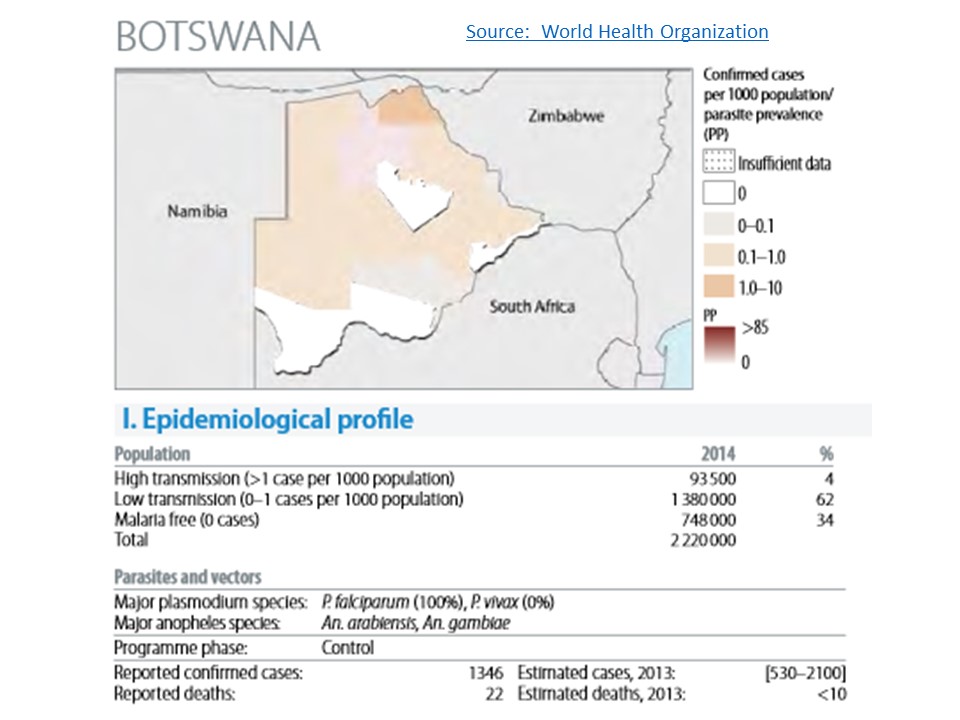

Lucky for me and anyone else who lives here, Botswana has been immensely successful in the battle against malaria. In 2013, there were 1346 confirmed cases and 22 deaths from malaria in Botswana according to the World Health Organization. The total population of Botswana in 2014 was 2,220,000. So 1346/2,220,000 = 0.06% of the population (or 6 in 10,000) got malaria in 2013. If this was flu in America, it would be considered a pandemic, but for me, I decided I could accept the risk and avoid taking Lariam or 7 months of antibiotics (also used to prevent malaria).

In addition, I visited a Maun doctor two weeks after we arrived, to get her informed opinion on local malaria risk. We are in the more malaria-prone northern area of Botswana and I wanted to know what she thought. She says she hardly ever sees cases, even when working in the University hospital.

Additionally, the diagnosis for malaria is quick and easy. If a patient presents with high fever, the doctor takes a blood sample and views it under a microscope for presence of the malaria parasite. My Maun doctor assures me that the test takes 30 minutes. Most cases she sends for malaria testing are in fact flu. If you get malaria, you can take a 3-day course of Coartem, also available locally for about US$32 (a huge price for many local people). The doctor recommended I buy Coartem now and carry it with me, particularly when I am working in the field, far from medical care. So I did. I bought two boxes just in case, and I have a thermometer to detect a rising fever.

It also helped that the doctor gave me her cell phone number and promised to take me to the hospital, oversee my care, and hold my hand if I actually did get malaria. What a wonderful, reassuring thing.

Interestingly, there are 1500 cases of malaria in the United States every year, mostly affecting travelers who picked up malaria in the tropics and brought it home. You can develop malaria as soon as 7 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito. For most people, symptoms will begin 10 days to 4 weeks after being bitten, but it can take as long as a year for the disease to manifest itself. So, it I get a fever next year, after I go back to the U.S., I’ll need to mention the possibility of malaria to my American doctor. No doubt that will add a little spice to his day!

So why don’t these 1500 cases explode into malaria epidemics in the U.S.? We have the right mosquito species to vector the disease, and goodness knows there are plenty of them.

Malaria was, in fact, an issue in the U.S. until 1954. Most people will (perhaps incorrectly) link this success to the spraying of pesticides. Like Botswana, the U.S. maintains comprehensive pesticide spraying programs to kill mosquitoes, relying mainly on pyrethroids sprayed from trucks into neighborhoods. We had that when we lived in Florida. Read my post on pyrethroids here.

Botswana uses pyrethroid-impregnated bed nets, which have been distributed for free since 2009. Botswana also sprays DDT into houses and huts where people live. The approach, called Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) is approved by the World Health Organization.

I will say that the nets do work. We slept under impregnated nets our first night in Botswana. In the morning, the floor was littered with the carcasses of 300 mosquitoes, maybe more, evidence that the pyrethroids were working. We also did not have any bites – a good outcome that would have been achieved with an untreated net also.

As with all selective pressures, mosquitoes in Botswana are becoming resistant to pyrethroids. It makes sense. The few mosquitoes who happen to have the right body chemistry: suites of enzymes that break down or eliminate pyrethroids, will be the ones to survive and make babies. They will pass their pesticide resistant chemistry to their offspring and slowly take over the world.

But there is something more interesting in the story of how America got rid of malaria, and why it doesn’t come back, despite helpful travelers like myself who unwittingly aid the import of malaria.

In 2002, the mosquito genome was sequenced and the triumph published in the October 4 issue of the Journal Science. I was a graduate student at the time and I happened to read that issue as I prepared for my qualifying exams – a nerve-wracking 3 hour oral test where you meet with 5 faculty who ask you a zillion questions about your research and then decide your fate (pass and be allowed to write a dissertation, or fail and be sent away to some other form of employment).

On page 86 of this issue of Science, I read something that has stuck with me always. Here is an exerpt from the article, written by Stephen Budiansky and found in its entirety here.

The incidence of malaria began to decline dramatically in industrializing nations toward the end of the 19th century, well before mosquito-control programs began—indeed, before mosquitoes were recognized as carriers of the disease. Better housing and sanitation played a significant part, but nothing did as much as the advent of one remarkably simple device in the early 20th century: the window screen.

Breaking the chain of transmission was the crucial factor. If each infected person transmitted the disease on average to fewer than one other person, the epidemic would be broken and the population of the disease-causing organisms would not be able to sustain itself. That is what ultimately happened. As Spielman notes, the mosquito survived, but the parasite it transmitted did not.

To illustrate his point, Budiansky describes the example of dengue fever along the Rio Grande. Dengue is also a mosquito-transmitted disease.

From 1980 to 1999, there were 64 cases in Texas versus 62,514 in the three Mexican states on the other side of the [Rio Grande]. Yet the population of dengue-carrying [mosquitoes] is actually greater on the U.S. side. The crucial difference is that in Mexican towns and cities, window screens are rare and people are constantly out on the streets exposed to the disease carriers.

It seems that the window screen is a critical weapon in the fight against malaria! Despite Botswana’s success with lowering malaria rates, there are still very few window screens here. My house has none and that is typical. We close our windows at dusk and put on the air conditioning (lucky us – most people just swelter and get bitten). In fact, I saw my first window screen ever in all my time in Africa (including my childhood) when I moved into my office at the Okavango Research Institute. Weird – my office is in a temporary trailer, but I have a screen!

Coming from America where screens are everywhere, the lack of screens here, in a malaria prone land, is remarkable to me. The same observation of no window screens was published last week by a visitor to Brazil, where the mosquito-borne Zika virus is making headlines.

Back in 2002, when I was a graduate student reading Science, I wrote to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. They fund a lot of malaria research and pour money into preventing and treating malaria on the ground. I suggested they start distributing window screens and help people improve the quality of their housing so that screens are effective. The Foundation wrote back to say they appreciated my suggestion and would file the idea.

It was nice to get a response.