April 7, 2016

At last, fish in our nets and no crocodiles!

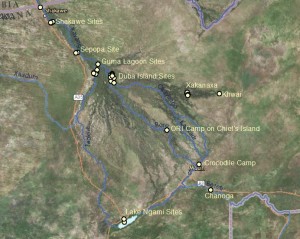

We finally had a good catch near Xakanaxa – 15 tilapia and 14 other species. The secret seems be going to the flood plains where the water is shallow (less than 1 meter) and there is lots of emergent vegetation – grasses and a variety of water lilies predominate. The flood has come to Xakanaxa, evidenced by the low oxygen in the flood plains. Low oxygen (3-4 mg/L) didn’t seem to deter the fish since they were there and they were obviously alive.

Our outdoor laboratory was busy all day. It took until 5 pm to process all the fish and clean up. Once the sun sets, the work day has to be done.

At 5 pm, my two colleagues went off to help a friend of theirs, leaving me alone at the boat launch. Eyeing the bush around me suspiciously, I packed up the last of our supplies and samples. A small group of plump birds fluttered around, engaged in a mating dance that made them oblivious of me. Before dark, I walked back to the campsite, relieved to note that we had (human) neighbors for the night, who could keep me company from a distance while I wrestled the campfire back to life.

That night was just as exciting as all the others. We cleverly put our pots away, so no clattering, but the hyenas came in to check out the camp just in case. There was a loud sniffing at my tent zippers at one point, making them clink against each other. A little unnerving, but the zippers were shut tight, and whatever it was moved on. Lions roared in the distance, but unlike at Chief’s Island, this pride was far away.

In the morning, after saying hello to the elephant near the bathrooms, we packed up camp and headed out for one last round of water quality measures at our five sampling sites. It was a glorious morning, sparkling, cool, fresh. We worked through the sites, spotting red lechwe antelope at site 4 on the flood plain.

When we were as far away as possible, the boat engine died.

That’s right – it did not start at all. Not a murmur, not a burp. Just silence, leaving us staring at it and wondering what to do. Well, we could stay there, dehydrating in the warming sun or we could do the aquatic equivalent of walking. We could pole home.

In Botswana, people use long (3 meters or longer) wooden poles to push narrow canoes through shallow wetlands. We carry two poles with us on the boat – mostly for pushing away from shore or getting ourselves unstuck if we accidentally beach the boat in too-shallow water. Today we also had an extra-long piece of PVC pipe that we planned to use later for housing a data logger. Three poles for three polers.

Off we went, at 1 km an hour for a nice 6 km ride. It was fine at first because the slow pace gave me ample opportunity to really look at the water and the plants, to feel the variation in depth and substrate (river bottom) as we glided across the surface, to notice tiny fish hiding in the water lilies. But after an hour, we were starting to tire and were looking forward with skepticism to the distance still to be crossed.

After 90 minutes, another boat showed up. Thank goodness. They were a nice burly boat with a big motor, carrying lumber to a wilderness camp. They were exceedingly kind to give us a 20 minute tow back to our camp, effectively rescuing us from an all day, unplanned poling adventure. “What an adventure,” said one of our rescuers, grinning at the sweat on our brows.

With our poling excursion behind us, we left Xakanaxa Camp and drove on to Khwai, where the parallel running river crosses the road. It’s 42 km of sand track that takes at least two hours. We took the “dry” route, so my colleague only had to wade once along the road to determine if the car could navigate the “puddle”.

Khwai is a small village, located a few km from Moremi North Gate, across an extra sketchy bridge. We crossed this bridge once, pulling a trailer with a boat.

At the other side, we bought cokes at a shop that powered its fridges with solar power, and then we drove back again across the same sketchy bridge! It held up both times and we had no disasters, so I am obviously way too picky about bridges.

It was 8 pm by the time we rolled back into Maun, having seen magnificent kudu, delicate impala, imposing buffalo, curious hornbills, and loads of zebra and giraffe along the way. I was glad to get home and sleep in a soft bed. I like the camping and the not camping. At home, the only wildlife that wake me up in the night are mosquitoes.