June 3, 2016

By 3 pm we were barely half way there. Our speed picked up in places but rarely lasted more than five minutes. Getting to ORI’s camp on Chief’s Island is tricky when the flood first comes. It’s too wet to drive and not flooded enough to boat. Interestingly, our return trip just three days later was much easier. The water had risen just enough to elevate out boat and speed our passage.

This trip along the Boro would prove one of the most exciting of my entire expedition to Botswana. As our boat slowly made headway along the winding channel, we encountered hippos, river monitors, elephants, herds of graceful red lechwe, crocodiles, burned grasslands and wildfires, and dramatic palm-studded landscapes. The river was changeable and erratic. Sometimes broad and flowing with long range views across the savannah. Sometimes enclosed in a dense and narrow tunnel of tall grasses, barely wide enough for the boat to pass. Sometimes nothing more than a shallow flooded plain.

It struck me that meeting a hippo in the tunneled narrows would create an unwinnable conflict. Unwinnable for us anyway. The hippo would take up the entire spans of the channel and given the twisty-turny hydrology, we would have no warning of his presence until we met him face to face. There would be nowhere for us to go if the hippo flipped our boat. The tall flooded grasses on either side of the channel would be pokey, treacherous, and inhabited by other toothy creatures. Other than that, there was the channel and an unknown distance to dry land.

My friend in Maun told me a hair-raising story about a retired couple on their Africa trip-of-a-life-time. They had departed on a guided mokoro (canoe) trip into the channels of the Delta. Under the vast blue sky, they glided silently over the water. Herons flew overhead. Red lechwe grazed on the banks.

And then the boat jerked forward.

On guided mokoro trips, the passengers (usually one or two) sit in the front of the canoe. The guide stands in the back where he can steer and push the boat using a long wooden pole. In this instance, the retired couple glanced back at their guide who assured them that everything was fine. Some minutes went by and there was mild splash that caused the boat to bounce. When the passengers looked back again, the guide had vanished. There was no one there, no sign of anything. No struggle, nothing in the water, no explanation whatsoever.

Then, without warning, the boat abruptly flipped and our retired couple found themselves standing in waist-deep water, their tossed canoe foundering nearby. Still no sign of the guide. No evidence on an animal – a hippo or more likely a crocodile. Instead, a gentle breeze ruffled the water. Bees buzzed in the morning glories strung along the grassy edge.

One can only imagine the ominous foreboding that must have descended at that moment. The water of the Okavango is so clear, you can see your feet and everything else below the surface. It would be no problem, for instance, to find your overturned lunch box or your lost sneaker. The couple probably made a panicked dash for their boat. The story goes that they could not get back into the canoe. They could right it, and one person could climb in while the other steadied the boat. But when the second person tried to get in, the mokoro flipped again. This effort might have gone on for hours. Or they gave up and just stood there in the water, wondering what happened to their guide. The wilderness had swallowed him in a blink and left no trace.

After four hours, the couple were found by a passing safari group. They were wet, probably chilly, a bit sunburned, in shock, but physically intact. They were rescued and returned to dry land and a hot meal. The guide was never found. For his family, the ending was much worse.

If you go to Africa, there will always be stories like this. One in a thousand mokoro trips ends like that, maybe one in 10,000. But they are the stories that make the wilderness wild. They remind us that we are not special. We are part of something much larger than ourselves. And they argue for caution, respect, and good judgement. They are the reason you always arrive at your destination before the sun goes down.

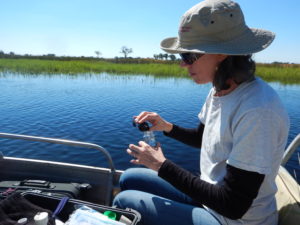

And there we were, cruising along the Boro, watching a glorious sunset, swatting the hordes of mosquitoes taking flight as we puttered by, clutching the GPS tightly to our collective chest. Seven kilometers to go. We would never arrive before sundown. I also needed our last water sample, which I decided to collect on-the-go rather than stop the boat at this late hour.

My thoughts on how to measure dissolved oxygen from a moving boat were interrupted by the boat stopping at the edge of a mass of grass. Swarms of mosquitoes rose from the swamp and descended on our warm and blood-filled flesh. “The channel is closed,” declared Mos. At that moment, the last shred of light on the horizon faded into night.

We turned on our headlamps and surveyed the problem. I took my oxygen measurement. Might as well. The boat wasn’t moving. I collected the water sample and replicated measurements of pH, temperature, total dissolved solids, and conductivity that were taken when the boat was still moving. The channel was indeed closed. It had happened in the last week, since Mos’s last visit. As inconvenient as it was, particularly in the dark, it was also magnificent to witness.

The changeability of channels in the Delta is one reason the place is so spectacularly diverse. Channels close and open all the time. Hippos and elephants are important engineers of new channels as they trample, cut, and eat plants. Old channels close when grasses fill them in. Channel movement facilitates full use of the Delta by wildlife as well as broad resource distribution; the biodiversity of the Okavango depends greatly on the changeability of its hydrology.

I thought about explaining this to my guests but decided this wasn’t the time. At that moment, we were being sucked dry by a thousand mosquito-borne hypodermic needles. It was dark. We were one kilometer away from our camp and our passage was closed. A hippo grunted nearby.

Mos yelled out into the darkness and a distant voice answered. Lights flashed on the faraway shore and a boat engine roared to life. The camp caretakers were expecting us and had anticipated our predicament. They had been waiting for us.

They came through one of the side channels, using the weight of the boat to push back the grasses. Mos turned our boat and headed towards them. After 20 minutes of revving engines and wacking grasses, we popped out into an open lagoon and closed the short distance to the camp. We were greeted with amusement and a large amount of hand shaking. I had met everyone before but this was Brandon and John’s first visit. We gathered our supplies, pelican cases, tents, coolers, bottles of water, and luggage, and finally found ourselves standing in the middle of ORI’s camp on Chief’s Island. A hippo grunted in the channel, the campfire crackled, a lion roared in the distance. Relief, happiness, gratitude, a brief rest and then we worked.